Civic Caucus Internal Discussion and John Adams Q and A

What else do we need to learn about low-income housing issues?

A Civic Caucus Internal Discussion

July 26, 2019

In October 2018, the Civic Caucus began examining the topic of affordable/low-income housing. The Civic Caucus has interviewed the people listed below in an effort to gain a deeper understanding of this complex area and to share it with our readers. Notes of the interviews are available on the Civic Caucus website and by clicking on the links below:

* Jim Solem, Former Commissioner of Minnesota Housing Finance Agency-- July 19, 2019 (Interview notes forthcoming);

* Mark Wright, Federal Reserve -- July 12, 2019 (Interview notes forthcoming);

* Owen Metz & Paula Prahl, Dominium -June 21, 2019;

* Commissioner Jennifer Ho, Minnesota Housing -May 31, 2019;

* Steve Wellington, Wellington Management -May 3, 2019;

* Lee Blons, Beacon Housing -April 5, 2019;

* Tim Marx, Catholic Charities -March 8, 2019;

* Chad Schwitters, Urban Homeworks -February 22, 2019;

* Steve Horsfield, Simpson Housing -January 25, 2019;

* Mikkel Beckman, Hennepin Housing Coordinator -January 18, 2019;

* Jon Gutzman, Saint Paul Public Housing -December 7, 2018;

* Greg Russ, Minneapolis Public Housing Authority -November 16, 2018;

* Jon Commers & Libby Starling, Metropolitan Council -November 9, 2018;

* John Adams, Emeritus Professor , University of Minnesota-November 2, 2018.

The Civic Caucus met for an internal discussion on July 26, 2019, to clarify its direction on the affordable housing issue, decide on the next steps it should pursue on that issue and consider what kind of end product we might produce. Emeritus University of Minnesota Professor and Civic Caucus interview team member John Adams prepared a memorandum on July 17, 2019-prior to the meeting-to capture the learning thus far and serve as a discussion platform. He wrote the memorandum as a series of 24 questions and answers.

Part One of these notes highlights the July 26,2019, internal discussion. Part Two reprints in full John Adams' July 17, 2019, memorandum.

Part One.

Highlights of the July 26, 2019, internal discussion.

Present

John Adams, Steve Anderson, Janis Clay (executive director), Pat Davies, Paul Ostrow (chair), Clarence Shallbetter, TWilliams. By phone: Paul Gilje.

Discussion

The group began with thanks to John Adams for his detailed memorandum, which can be read in full in Part Two. Adams' memorandum illustrates the complex landscape of the affordable housing issue.

"Affordable Housing."

Adams cautioned that the often-used umbrella terms "affordable housing" and "affordable-housing crisis" are simplistic and not helpful. The issues surrounding affordability and low-income housing are highly complex, a series of ongoingproblems thatdiffer from one another, differ from place to placeand invite different responses and solutions.

There was general agreement that the term "affordable housing" is a generic one, consisting of many different groups of people. Their common characteristic is having low incomes. Some-physically disabled persons and veterans, for example-have substantial housing programs targeted at them.

A helpful approach is to look at the issues from two sides, demand and supply, both addressed in great detail in the Adams memorandum.

The Demand Side.

On the demand side, the Civic Caucus interviews illuminate deep and long-standing challenges people face. A fundamental question is why so many people lack sufficient financial resources to successfully enter the private housing market. The issues range from physical, emotional, family and chemical challenges to gaps in marketable skills and "soft" skills. Importantly, people making up the different groups vary greatly in their income-earning potential and in their knowledge and ability to handle their financial and other affairs.

In his memorandum, Adams separates those needing housing into a taxonomy of 10 types of individuals and households. Included in these categories are the following: (1) youth who leave home by choice or due to challenging home situations; (2) people of working age who are underemployed or unemployed, due to such factors as physical, emotional, chemical dependency and criminal backgrounds; (3) people who lack marketable skills and/or "soft skills"; (4) people who work and manage their lives well, but earn so little they cannot afford housing at market prices; (5) low-income people with children, who are working or receiving assistance payments; and (6) elderly singles and elderly couples living on limited income and perhaps meagersavings. Importantly, each category invites different kinds of housing policies and different housing solutions.

The unmet demand for low-priced housing also varies from place to place within the large Minneapolis/Saint Paul metropolitan area (home to nearly 3 million people in seven counties and 182 communities spread over nearly 3,000 square miles) and outside the metro area. This demand has changed greatly over time as population size, household size and household composition have changed.

Purchasing power for low-income persons and households is enhanced by county public-assistance payments and most significantly by the federal Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program. The demand for vouchers by eligible households vastly exceeds the available funding.

The Supply Side.

The supply side is also tremendously complex. With households trending smaller, the demand for housing has risen faster than the population. Nonprofit and public housing organizations face constraints by way of insufficient federal and state money to subsidize their supply-side operations. The cost to produce new housing is high, influenced by factors such as land cost, zoning and building codes, labor and material cost, etc. There are also significant incentives to build large and expensive homes. This comes from the economics of building (it is less efficient to build smaller square-footage buildings) and from federal subsidies like the mortgage-interest deduction.

The single most important current tool to stimulate the development and rehabilitation of affordable housing is the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), which was established as part of the tax reform act of 1986. This program currently finances about 90 percent of all new affordable housing development. The tax benefits accrue to the developers and the rehab industry, rather than directly to the housing recipients.

There is great temptation to focus largely on the supply side, housing affordability, rather than to tackle the root causes of the persistent issue of poverty-why are there so many individuals and households who are poor?

Areas that Merit Further Exploration

Continuing Maintenance and Management.

There was general agreement that the Civic Caucus has not adequately discussed and does not fully understand the topic of management of multi-occupant housing, how it is done and its cost, as well as the continuous maintenance of these buildings. It is essential to acknowledge and realistically address the challenges faced by those who lack basic skills to maintain housing once they have it and who face challenges living in community and being good neighbors. Structures must be in place for maintaining and managing the housing that is produced. Management is key, which often should include 24-hour staffing. This is expensive, but essential to maintain order and livability for all. This becomes ever more important with increasing density.

Other Topics.

Other topics the Civic Caucus needs to examine in greater depth include housing finance and the component costs that private-sector builders face in producing various kinds of housing. That should include their reflections on the many proposals for reducing rents in multi-occupant buildings for some lower-income occupants. The topic of building codes and zoning as they affect housing costs should also be clarified. Another topic might be to look at incentives for development of duplexes and triplexes that confer equity to the owners, as well as greater use of manufactured housing to address the housing affordability challenges for many groups.

Those Left Out.

Supportive housing advocates are doing effective work helping groups such as veterans, families with children and people with disabilities. But single adults of working age are not receiving much of this support. In the past, the rooming-house model provided at least the option of a single secure room, a shared bath and a place to store belongings. While this "single-room occupancy" model had its limitations, it filled a certain need. Due to factors such as zoning, urban renewal projects and neighborhood opposition, rooming houses have become very scarce. There seem to be fewer advocacy and supportive housing groups looking out for this category of people.

What Next?

A member of the interview team noted that reaching any sort of consensus is highly challenging in this complex area. Does this issue illustrate a need to bring back the State Planning Agency? How about the role of the Metropolitan Council, which has had a large recent turnover? Do other states have models we should look at and possibly replicate?

One member observed that what's important with our inquiry is to share our learning with others. This may be at least as important as attempting to distill a set of recommendations on what further to do. Others felt a set of recommendations is something some might be expecting from the Civic Caucus.

Gaining an understanding of the dimensions of a variety of housing challenges has taken considerable time for the Civic Caucus. Members are now better able to engage in an active discussion with many in the housing field.

How long should the Civic Caucus continue to explore the affordable housing topic? This is a large and complex discussion and we have not yet addressed or not adequately explored many aspects. We need to think carefully about what of value the Civic Caucus has to contribute and how long we should continue with this topic.

Part Two.

"Civic Caucus Exploration

of the Affordable Housing Topic"

by John S. Adams, July 17, 2019.

(24 Questions and Answers)

(1) What exactly are the main features of what's called the "affordable housing crisis," which many claim is afflicting Greater Minnesota and the Twin Cities Area?

A: First of all, we don't face a "crisis" (which is an over-used and misused word). What we have is a series of ongoing problems that differ from one another, differ from place to place, and invite different responses and solutions.

(2) What triggered the Civic Caucus housing study?

A: Our exploration of the topic began in fall 2018 as a well-publicized encampment of homeless people, largely native people from the Twin Cities and some from Minnesota and Wisconsin Indian reservations, developed and expanded during the preceding summer along the Hiawatha Avenue freeway in South Minneapolis.

(3) Fair enough; what has been the Civic Caucus approach to this specific event and related challenges?

A: There are two main approaches to the housing challenges faced by manyindividuals and households: there's a " demand side"-people lacking sufficient financial resources to enter the private housing market satisfactorily, and there's a "supply side"-too few available units at prices low-income individuals and larger households can afford and too few at locations where they prefer to live.

... And each side has several distinct components.

(4) OK, start with the demand side; what folks are we talking about, and what are their challenges?

A: In our weekly Civic Caucus meetings, most of them with experts in various parts of the of housing industry, we tried hard to get those visiting our interview group to help us develop a taxonomy of the typesof individuals and households that encounter challenges when locating, obtaining and retaining the housing they want and feel that they deserve and can afford. The 10 main groups include:

- Individual boys and girls who have left home-sometimes by choice ("runaways"), sometimes because they were told to leave the home for different reasons;

- Individual men and women of working age (16-65) who are unemployed or underemployed, often with physical handicaps, emotional handicaps, personality disorders, or chemical dependency problems (drugs, alcohol), felony convictions, or other special needs or backgrounds that interfere with regular employment, which in turn lead to limited or irregular income;

- Individual men and women of working age (16-65) who are unemployed or underemployed, with deficient education and job training, who lack marketable skills, or have the skills but have spotty employment histories, or have limited incomes because they lack what employers call "soft skills"-that is, the ability to arrive to work on time, get along with co-workers, follow instructions, continue working conscientiously when unsupervised, etc., and lose jobs as a result;

- Individual men and women of working age (16-65) who work regularly and manage their lives well, but earn so little that they cannot obtain the housing they feel they need at prices they can afford to pay, given their other spending priorities and commitments;

- Family and non-family (i.e., unrelated) adult households (i.e., two or more low-income, working-age people who are working);

- Family and non-family adulthouseholds (i.e., two or more working-age people not working but receiving welfare payments);

- Low-income family households with preschool children;

- Low-income family households with school-age children;

- Elderly singles living on limited income from Social Security, modest pensions, and perhaps meager savings;

- Elderly couples living on extremely limited income from Social Security, modest pensions, and perhaps meager savings.

These 10 types of low-income households vary significantly in their ability toobtain satisfactory and reliable incomes, and in their knowledgeand ability to handle their financial and other affairs. For example, many elderly singles and couples have low incomes, but their monthly payments from Social Security are secure and Medicare can be relied on. Such households may be knowledgeable and highly skilled in managing money, shopping, cooking their own meals and managing their affairs, even though they have little money. Their situations differ from many younger individuals and couples whose low incomes are unreliable and for whom timely access to health care is a continuing challenge.

In a second example, low-income single parents or couples with school-age children face serious challenges trying to provide stable housing so that their kids can enjoy a stable school experience month after month, year after year.

A third example comprises single men or single women of working age, or elderly people with chemical dependency problems, who often want and need only a single secure room with shared bath and a place to store their belongings, but such "single-room-occupancy" opportunities are scarce.

Each of the 10 situations differs from the others and invites different kinds of housing policies and housing solutions.

(5) The Metropolitan Council has responsibility for providing selected services and overseeing planning for an area that contains seven counties and 182 municipalities, in an area of nearly 3,000 square miles. It also is the public housing authority for cities lacking their own housing authority. How does the unmet demand for low-priced housing vary from place to place within this large area?

A: The Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area is home to nearly 3 million people living in seven counties and 182 communities, spread over nearly 3,000 square miles. Most residents, regardless of income, have only limited familiarity with places distant from their local neighborhood. For example, the distance between Orono and Stillwater is 44 miles, between Eden Prairie and Mahtomedi is 38 miles, and between Anoka and Burnsville in 37 miles, yet all are within the Twin Cities area. A low-income household in East Bloomington will generally be unaware of housing opportunities in Coon Rapids-or even know where it is.

On average, low-income individuals have less-than-average knowledge of places beyond their familiar neighborhoods, so they typically seek housing within areas known to them, which also are the areas where their friends and relatives typically reside.

(6) How does the demand for low-priced housing vary over time as population size and household size and composition have changed?

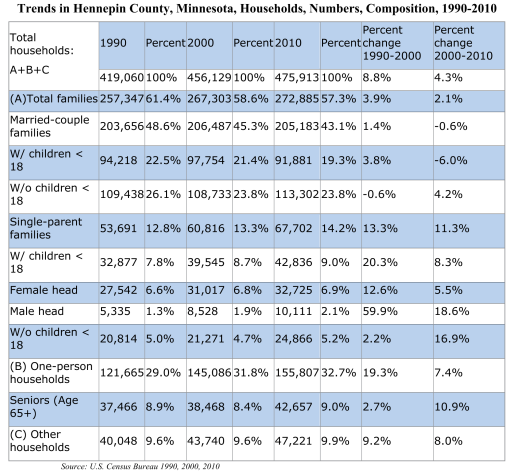

A: Let's take a look at Hennepin County, for example. It's the largest county in the metro area and recent trends in the county illustrate various features of population change that affect housing demand, irrespective of household purchasing power.

- Between 1990 and 2000, the county population rose from 1.034 million to 1.118 million, or 8.1 percent, while the number of households rose 8.8 percent.

- Between 2000 and 2010, the county population rose from 1.118 million to 1.154 million, or 3.2 percent, while the number of households rose 4.3 percent.

In other words, the demand for housing has been rising faster than the population, a trend that apparently continued after 2010, as household sizes have continued downward-from 2.47 in 1990, to 2.45 in 2000, to 2.42 in 2010. The decline is a consequence of more people living alone-a share of households magnified by single elderly living longer lives, plus couples of all compositions having fewer or no children.

See table below showing these trends for Hennepin County.

(7) How do public agencies enhance housing purchasing power for low-income individuals and larger households?

One source is public welfare payments by county welfare agencies, but the main source is the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program.

(8) Explain the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program and how it works.

A: The name comes from language in Section 201 of Title 2 of Public Law 93-383, also known as the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 . This law amended the Housing Act of 1937, the second piece of housing legislation in America'shistory. The first was The Housing Act of 1934, part of Roosevelt's New Deal.

The Section 8 Housing Voucher program will pay the balance of a rent payment that exceeds 30 percent of a renter's monthly income. The rental unit must be inspected and approved by the local housing authority and the rental amount must be at or below the Fair Market Rent set by HUD. Households apply to their local housing authority for a voucher. Demand for vouchers vastly exceeds the supply of vouchers.

A voucher, once received, helps low-income, senior and disabled households afford safe and secure housing. Assistance through the voucher program allows voucher holders to find and rent their own housing, as long as the unit meets HUD requirements.

The program is administered by local housing authorities, such as the Minneapolis Housing Authority or the St. Paul Housing Agency. Each housing authority has different preferences and requirements, based on their service areas' affordable housing needs. The local housing authority defines the details on how to qualify and apply for the Section 8 Housing Choice voucher program.

Money to support the voucher program comes from HUD and is limited. Housing authorities must apply to HUD for voucher money. The demand for vouchers by eligible households vastly exceeds what housing authorities want and need.

(9) What about the supply side? What kinds of housing are available in the metro area's housing inventory?

A: Start with an example. Hennepin County's population in 2000 was 1,116,039 and by 2010, it had risen to 1,152,425, an increase of 3.26 percent.

Meanwhile, the number of housing units in the county increased from 468,826 to 509,469, an increase of 8.67 percent.

But neither of these numbers and rates of increase mean much in themselves. The main point is that during the decade, householdshave continued their long-term trend of getting smaller, meaning that the demand for housing units at all price levels has expanded faster than the rate of increase of the population. [https://www.huduser.gov/periodicals/USHMC/reg/MinneapolisMN_HMP_July15.pdf ]

(10) Describe the housing inventory and how it changes through time.

A: There are four parts to the housing inventory and ways that the inventory changes over a decade:

- New housing units are built-singles, doubles, multiple-unit structures;

- Units are demolished (or converted to nonresidential uses);

- Units are consolidated (e.g., two apartments made into one); and

- Units are subdivided (a single-unit-a house or apartment-is divided into two units), or a large house is turned into a rooming house, so one unit becomes two or several units.

The decennial U.S. Census of Housing, supplemented by the American Community Survey, includes conventional single-unit detached and attached houses, duplexes, triplexes and four-plexes, plus apartments, condos and mobile homes. But it also includes in the housing stock jails, prisons, convents, monasteries, nursing homes, orphanages and similar facilities, college student dorms, and crews on vessels (e.g., ocean-going ships at the Duluth-Superior harbor; not relevant for the Twin Cities). None of these comprise a significant element of the housing stock in the Twin Cities area nor of the low-income inventory relevant to our policy inquiry.

(11) How does the location of the various parts of the metro area's housing stock matter?

A: The housing inventory is arrayed across the entire Twin Cities area of almost 3,000 square miles. But it is composed of a series of relatively discrete areal submarkets that in many respects (less today than in decades past) involve internal demand/supply relationships that play out relatively independently from other submarkets.

esearch carried out at the University of Minnesota in the 1970s and 1980s disclosed that most moves are short moves. When households relocate within the metro area, the vast majority move within one of 14 submarkets, half of them on the St. Paul side of the metro area and half on the Minneapolis side. Each submarket is roughly wedge-shaped, with its origin on the edge of a downtown, and extending outward and widening toward the suburbs.

Households traditionally have tended to move outward to newer or larger or more expensive units as means, wants and tastes have dictated or inward, as household sizes declined or financial resources diminished.

The structure and operation of these housing submarkets were shaped initially by the structure and operation of streetcar lines that radiated outward from the downtowns, responding to the in-out orientation of residents and workers during the heyday of the streetcar era (1890s-1950s). They were reinforced by later highway construction and highway use since the 1960s.

(12) How do the housing sectors differ from one another, aside from differences in number of households and number of housing units?

A: There are two important features of the dynamic structure of these housing submarkets that distinguish them from one another and that affect their operation. First, each of them traditionally displays a distinctive socio-economic class of residents, based on the early history of the cities and their inner neighborhoods next to the downtowns. Some sectors attract, house and retain the elite, some are dominantly upper-middle class, some are middle- and lower-middle class and some have traditionally been distinctly working class in their dominant composition.

Each sector tends to extend its character into its nearby suburbs, populating suburbs that are distinct in their socio-economic status. No one who knows our metropolitan area would argue that there is little difference between Coon Rapids and Edina, or between West St. Paul and Roseville. On the other hand, as the second- and third-ring suburbs have sprawled outward, the distinctiveness of the suburbs on a social-class basis has steadily muted, with many suburbs displaying more differences within than between them and their neighbors.

(13) How-and where-did the construction of new housing on the suburban edges end up delivering low-cost housing in the inner cities from the 1950s until recent years?

A: The second important feature distinguishing the sectors from one another has been the different rates of construction of new housing on their suburban edges between the 1950s and the 1980s. The strongest markets for new tract housing produced by the major merchant builders, such as Orrin Thompson, Vern Donnay, and Pemtom, were on the edges of the middle- and upper-middle-class sectors of Minneapolis and St. Paul. There were four prominent such sectors. First was one extending south from downtown Minneapolis, through central south Minneapolis into central Richfield, through central Bloomington, to Burnsville and eventually Lakeville.

A second middle-class sector extended to the northwest, originating in Near North Minneapolis and spreading into Golden Valley, Crystal, New Hope and Plymouth.

In St. Paul, two more middle- and upper-middle class sectors flanked the elite Summit Avenue, one extending west and southwest into Macalester Groveland, Highland Park and eventually into Mendota Heights. The fourth originated west of downtown St. Paul, north of Summit, through Como Park, St. Anthony Park, Roseville and Shoreview.

Vigorous land development and new housing construction in the suburban areas of these four sectors drew outward thousands of households with the financial means and the desire to move upward-and outward .

As they moved outward, they released thousands of housing units, making them available to others wanting to move in to take their places.

As the vacancies created by new suburban housing construction proceeded apace in the decades after World War II- rates of construction that exceeded net rates of household formation- the inner neighborhoods of those four sectors experienced significant surpluses of housing units, compared with availabledemand. That led to sharpdrops in price, which attracted low-income newcomers to these naturally occurring low-priced housing units-some single-unit houses, some units in multiple-unit structures.

This process delivered low-priced housing at steady rates to low-income households until recent years, when new housing construction rates began falling well short of the rates of new household formation. As a result, prices of all housing began rising steadily, which hit low-income individuals and households the hardest.

(14) What have we learned about the constraints that prevent an increase in the rate of construction of new subsidized or market-rate housing units?

A: We heard from the Minneapolis Public Housing Authority, the St. Paul Public Housing Agency, and from several nonprofit organizations that build or otherwise obtain and provide housing to low-income households and individuals. The main constraint they face is insufficient federal and state money to subsidize their supply-side operations.

We heard from two private developer-builders and have not yet obtained a full picture of their activities, or the nature of the constraints that exist that seem to prevent an expansion of their operations to produce market-rate new housing.

(15) What is meant by the "housing affordability challenge?"

A: We've talked about the various classes of individuals and households living in different parts of the metro area who encounter challenges locating, obtaining and retaining housing. We've also discussed the housing inventory divided up into a series of housing submarkets.

When we bring demand and supply together within the various submarkets, many low-income individuals and households find that they are unable to obtain housing at prices that they feel they can afford.

One indicator of housing affordability, recommended by the World Bank and the United Nations, rates affordabilityof housing by dividing the median house price in an area bygross [before tax] annual median household income.

Another common measure of community-wide affordability is the number of homes that a household with a certain percentage of median income can afford. For example, in a perfectly balanced housing market, the median household could officially afford the median housing option, while those poorer than the median income could not afford the median home.

Determining housing affordability is complex and has been contentious. The commonly used housing-expenditure-to-income-ratio tool has been challenged as it makes no allowance for household preferences and spending priorities or for variations in household wealth, among other considerations.

In the United Statesand Canada, a commonly accepted guideline for housing affordability is a housing cost that does not exceed 30 percent of a household's gross income . (Canada, for example, switched to a 25 percent rule from a 20 percent rule in the 1950s. In the 1980s this was replaced by a 30 percent rule.[ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Affordable_housing ]

(16) Minnesota Housing Commissioner Jennifer Ho told us that "Minnesota's housing market is limping broken,while California's is dead broken." Explain.

A: She stated that a healthy housing market consists of a rental vacancy rate of five percent and a five-month supply of homes for sale. She noted that rental vacancy rates are now even lower and most communities only have a one-month supply of homes for sale.

Ho told us that "a woefully inadequate number of housing units are being added in the state per year for the lowest-income people-those families earning 30 percent or less of area median income (AMI), or around $25,000." That level of income, she said, is where the housing market is most broken.

She went on to explain that Minnesota is 53,000 housing units-for all income levels-short of a healthy housing market and called on the Legislature to invest in a 10-year push to make the state's broken housing market healthy. A healthy housing market, she argues, is critical to the people of Minnesota and to the state's economic competitiveness.

Ho said in order to solve homelessness, we need (1) identify new sources of revenue, (2) reprioritize existing resources, or both, and (3) significantly increase investments to increase the supply of housing that is affordable.

Providing housing to people experiencing homelessness, she argues, is cost effective and would lower the costs of providing health care to them.

Ho discussed some of the reasons for the high cost of housing:

(a) Cost of land: The Metropolitan Council's efforts to contain low-density development on the edge of the built-up area by means of the Metropolitan Urban Services Area (MUSA) is based on the availability of sewer service in developing areas. It has the effect of limiting the supply of development land and thereby raises its price.

(b) Lack of productivity increases in the way we build housing : Building methods have changed little through the years, except in the case of factory-built houses, which most municipalities do not permit within their jurisdictions. Mobile home parks are similarly banned.

(c) Zoning Codes and Building Codes : Zoning ordinances that restrict certain areas of cities to single-unit houses can curtail an increase in multiple-unit structures. Building codes specify minimum standards for the construction of buildings. The main purpose of building codes is to protect public health, safety and general welfare as they relate to the construction and occupancy of buildings and structures.

(d) Labor Shortages: In recent years, builders consistently complain that the supply of skilled workers falls far short of demand for their services. Many say that they could and would build more houses if they could find the help.

(e) ising Cost of Construction Materials : The price of all building materials continues to rise and those costs are one component of the cost of building houses.

(f) Development-impact fees: In August 2018, in a ruling greeted as a victory for builders, the Minnesota Supreme Court imposed limits on how much communities can charge developers for the external costs that their new developments impose on existing residents of the community. These charges are called "development-impact fees," and cover the marginal costs to the community for roads, parks, fire and police protection, schools, extensions of water and sewer systems, and other municipal services. Such charges are generally not allowed in Minnesota because the Minnesota Legislature, unlike legislatures in over 20 other states, has failed to authorize them. [J.S. Adams and others. Development Impact Fees for Minnesota? A Review of Principles and National Practices . Report #3 in the Series: Transportation and Regional Growth Study. CTS 99-04. (Minneapolis: Minnesota Department of Transportation, Center for Transportation Studies). October 1999. 130pp]

"A suit filed by New Brighton-based developer Martin Harstad argued that he shouldn't have to pay for future road improvements outside a housing development he wanted to build in Woodbury. He sued after city officials said they wanted an additional $1.3 million in fees-about $7,000 per house-to help fund future improvements in other parts of the city.

"Many municipalities argue they are simply trying to ensure that such development and infrastructure costs will not be borne solely by all residents of a city in the way of higher taxes." [ Jim Buchta "A report commissioned by a builders group said municipal fees and regulations in the Twin Cities make it nearly impossible to build a single-family house for less than $375,000. StarTribune, 4 Feb 2019]

Ho also discussed the possibilities and concerns facing manufactured-home communities throughout the state. They provide housing, she says, although it's often substandard by some criteria.

(17) When new housing is built, why is it more profitable for developer-builders to construct larger and more expensive houses rather than smaller, inexpensive ones?

A: When new houses of different sizes are being built, as floor-area increases, the cost of construction rises arithmetically, but the interior size of the house rises geometrically. In other words, if the cost of building a 2,000 square-foot house costs X, the construction cost of building a 4,000 square-foot house of the same quality costs much less than 2X, but usually can be sold for a greater profit than two 2,000 square-foot houses.

Looking at the matter in reverse tells us that building a 1,000 square-foot house will not cost half that of the 2,000 square-foot house. Many building costs, like plumbing, wiring and utility hookups can be relatively fixed and do not decline proportionately as floor area declines with smaller units.

If this is confusing, think of a squarefield 100 feet on the side. It will take400 feet of fencing for a 10,000 square-foot field. A square field 200 feet on the side will require 800 feet of fencing for 40,000quare-foot field. In other words, only twice as much fencing isneeded for a field four times as big.

(18) Aside from what has been learned so far, what are the major remaining gaps that our visitors have not filled?

A: Many of our visitors pointed to the slowdown in housing construction and have asserted that if the volume of annual new housing construction were substantially increased, well ahead of net new household formations ,that would bring prices down, but we have received no systematic explanations for the slow pace of new housing construction.

Developers, builders and others point to (1) the cost of money, (2) the availability and cost of buildable land, (3) the cost of building materials, (4) the shortage of construction labor, plus (5) state and local development and building codes as restrictions on rates of new-house construction.

Developers, redevelopers and builders work with borrowed money. Building low-priced housing can be profitable only if money can be obtained at below-market rates. Such money is in limited supply. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program is a major source of low-cost money going into low-income housing projects.

(19) How does the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program work?

The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (Housing Credit) program is designed to stimulate investment in affordable housing in underserved urban and rural communities and in higher cost suburban communities across the nation. The program provides low-income families with a safe and decent place to live and, by reducing their rent burdens, it frees up income that can be spent on other necessities or put into savings for education or homeownership.

The Housing Credit is the single most important federal resource available to support the development and rehabilitation of affordable housing-currently financing about 90 percent of all new affordable housing development.

The LIHTC program was established as part of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 and is usually referred to as Section 42, which is the applicable section of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC). The LIHTC program provides tax incentives to encourage individual and corporate investors to invest in the development, acquisition andrehabilitation of affordable rental housing .

The LIHTC is an indirect federal subsidy that finances low-income housing. It allows investors in low-income housing to claim tax credits on their federal income-tax returns. The tax credit is calculated as a percentage of the costs incurred in developing the affordable housing property. The credit is claimed annually over a 10-year period. Investors who receive the tax credit from project sponsors are willing to lend money for low-income housing at below market rates because the money they save annually on their taxes justifies lending at lower interest rates. [ https://www.occ.gov/topics/community-affairs/publications/insights/pub-insights-mar-2014.pdf ]

The equity raised with LIHTCs can be used for newly constructed and substantially rehabilitated and affordable rental-housing properties for low-income households, and for the acquisition of such properties in acquisition/rehabilitation deals. To qualify for the credit, a project must meet the requirements of a qualified low-income project. Project sponsors/developers (project sponsors) are required to set aside at least 40 percent of the units for renters earning no more than 60 percent ofthe area's median income (the 40/60 test) or 20 percent of the units for renters earning 50 percent or less of the area's median income (the 20/50 test). These units are subject to rent restrictions such that the maximum permissible gross rent, including an allowance for utilities, must be less than 30 percent of imputed income based on an area's median income.

State housing agencies' selection procedures for tax-credit allocations often encourage project sponsors to provide more than the minimum number of affordable units and more than the minimum level of affordability. Because these credits are available only for affordable rental units, many applications designate 100 percent of units in properties as affordable and reserve some units for renters earning wellbelow 50 percent of the area median income.

Federal tax credits are limited in number and are allocated to state housing finance agencies by a formula based on population. The state housing agency (e.g., Minnesota Housing) then allocates them to project sponsors. Each state agency establishes its affordable housing priorities and developers compete for an award of tax credits based on how well their projects satisfy the state's housing needs.

Developers receiving an award provide the credits to investors in exchange for low-interest equity capital from the investors in their developments. Developers that receive tax credits then use the credits to reduce their federal income taxes. The tax credits are claimed over a 10-year period, but the property must be maintained as affordable housing for a minimum of 30 years.

Because tax credits can be recaptured for any noncompliance, investors maintain close supervision over the properties to ensure their long-term viability and compliance with IRS and state allocating agency requirements.

Units funded by the Housing Credit must be affordable for people earning no more than 60 percent of the area median income (AMI), although most residents have far lower incomes. Rent may not exceed 30 percent of the qualifying income.

What are the outcomes?

Since its inception, the Housing Credit has spurred the development of approximately three million quality homes for working families, seniors, disabled veterans, and people at risk of homelessness.

Each year, the Housing Credit finances about 100,000 units of affordable housing and creates approximately 96,000 jobs in the construction and property management industries.

Housing Credit properties outperform market-rate housing properties, with occupancy rates topping 96 percent and a cumulative foreclosure rate of 0.66 percent over the program's entire history.

The units tend to be occupied by very low-income families, with 48 percent of the units occupied by families making less than 30 percent of AMI; and 82 percent of the units occupied by families making less than 50 percent of AMI.

(20) What about low-cost money available from state and local sources for low-income housing?

A:

At the state level. Minnesota Housing (formerly Minnesota State Housing Finance Agency) obtains money from legislative appropriations and by selling bonds. The money raised is then loaned to agencies and organizations building low-priced housing.

At the city level. Housing and redevelopment agenciessometimes use the method of Tax Increment Financing (TIF) to lower the cost of producing low-income. It works like this: (1) The city passes an ordinance creating a TIF district containing land uses that are obsolete or otherwise ripe for redevelopment into housing. (2) The amount of current annual property taxes collected from the TIF district is calculated. (3) The city sells full faith and credit bonds to obtain money to clear the land and make it available for redevelopment. (4) The city sells the land to a developer at a below-market price. (5) Building of low-priced housing proceeds on the TIF site, perhaps accompanied by some neighborhood-service commercial activity. (5) The increment of annual real estate taxes collected from the redeveloped site that exceeds what had been collected prior to redevelopment, is assigned to pay interest on the TIF bonds and finance their eventual retirement.

(21) What about regulatory barriers and their effects on the construction of low-priced housing?

A: We have not explored this topic in any specific way, although a number of our visitors have mentioned regulations as an issue.

Developers, redevelopers and builders areoften highly constrained in what and how they can build, withtheir operations limited byhousing codes,building codes,neighborhood sentiments,off-street parking requirements, density rules and prohibitions against manufactured houses or mobile homes .

They are constrained in where they can build different kinds of housing (limited by zoning laws); and sizeof units that will be built-based on the economics of construction, because (as already discussed) cost per square foot ofliving space rises geometrically with reduced unit size; with the reverse encouraging large units because the costs of construction per square foot of interior living space drops fast as housing units become larger.

(22) Are there additional matters that we have not explored of discussed?

A: Neighborhood instability. Assessors, realtors, bankers, buyers,renters and neighbors understand that thevalue of a house plus the value of the lot on which it stands depend on not only (a) the features of the house itself, BUT also (b) what's happening and is expected to happen within the neighborhood setting (the socio-economic environment; nearby land uses; the natural environment; accessibility to desired destinations), which will affect the future value of the lot.

educed profitability of investing in apartment buildings. The 1986 revisions to the Internal Revenue Code substantially reduced the profitability of building and owning apartment buildings by eliminating certain treatments of passive losses and tax shelters for rental housing investors. This revision was followed by a spate of conversion of rentals to condos and a reduction in construction of new rentals that would otherwise have been built.

The new law contributed to the end of the real estate boom of the early-to-mid- 1980s, which, in turn, was the primary cause of the U.S. Savings and loan crisis . Prior to 1986, passive investors were able to use real estate losses to offset taxable income. When losses from these deals were no longer deductible, many investors sold their assets, which contributed to sinking real estate prices. [ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tax_Reform_Act_of_1986 ]

Long-term liability for construction defects. There have also been laws passed in recent years that extend for many years the liability for construction "defects" (some of which can be attributed to inadequate maintenance of buildings by condo associations) that builders of apartments and condos incur, which has curtailed new supplies of modest-price multiple unit housing. [ https://www.bizjournals.com/seattle/news/2018/09/19/what-contractors-need-to-know-about-the-risks-on.html ]

The role of cities' reliance on property taxes. 19th-century tax laws operating through the decades have prompted local units of government (cities, counties, school districts) to rely excessively on property taxes for their support. That has fostered a tendency for cities to "zone for revenue" (i.e., encourage land development that is expected to pay more taxes than it is expected to impose extra costs on the city, and vice-versa) in ways that discourage the construction of lower-priced owner-occupied and rental housing (e.g., manufactured housing and mobile homes on small lots).

This local fiscal environment encourages cities like Minneapolis and St. Paul to protect valuable residential neighborhoods because it is these very areas that produce the abundant revenues that the cities rely on to provide services to parts of the city unable to pay their way with the property taxes-residential and business-that they generate. [Alan Altshuler, Jose A. Gomez-Ibanez and Arnold M. Howitt. egulation for Revenue: The Political Economy of Land Use Exactions (Washington, D.C.: Brookings, 1994)]

The priority of housing among other household needs and wants. In the late 1960s, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development ran an experiment in a number of American cities and rural areas titled "The Experimental Housing Allowance Program." The idea was to identify low-income households who were living in squalid housing and give them cash to allow them to move to improved housing. What the study discovered was that a very large share of the households in the program spent the extra money on other stuff, like a more reliable car, which they valued more than better housing. This finding confounded the people running the experiment (and HUD officials, as well). The people running the study had priorities that were much different from those of the low-income households.

The persistent issue of poverty. The basic issue on the demand side of the housing matter remains: " Why are there so many individuals and households who are poor?" We seem unable or unwilling to tackle this problem directly, and as a result focus on things like "housing affordability" which is a complicated and misleading way to address a symptom of a situation, rather than going to the roots of the policy challenge.

That's one reason why elected officialsusually focus on " hardware solutions" (i.e., the SUPPLY side in the case of housing) for certain social problems, because they seem somehow more tractable and politically feasible. But as our 70-year experiment with public housing has taught us, building or financing public housing is exceptionally expensive, and many times it just doesn't work for certain types of households. But it does work for some.

Back in the 1960s or early 1970s,The New York Times reported that in the City of New York it cost the city's Public Housing Authority more to build and operate a unit of public housing than it would cost to buy houses in Queens and give them to low-income households.

There is much more that could be said about why we build what we build and where we build it, but one of the main features of new housing supply and market demand for it in the U.S. is that we build mainly large andexpansive houses because it's a very good economic deal for the middle-and upper-middle-class households who buy them. Since WWII, buyers of new housing, mainly in the suburbs, routinely get much more than they pay for because of a long list of subsidies from which they have benefited:

- Deductibility of mortgage-loan interest from taxable income.

- Deductibility of real estate taxes.

- Untaxed capital gains on residential real estate sales.

- Pre-1980 banking regulations that separated commercial banking (e.g., car loans; business inventoryloans, etc.) from residential housing finance (e.g., savings banks like Farmers & Mechanics; savings and loan associations) in ways that lowered the cost of mortgage loans to home buyers.

- VA Mortgage Guarantee & FHA Mortgage Insurance Programs.

- Average-cost (vs. full marginal-cost) pricing of utility extensions into developing areas.

- 1986 IRS Code, which permits borrowing on home equity for consumption, while allowing deductibility of mortgage-loan interest.

- For years, Minnesota rental housing paid higher real estate tax than owner-occupied housing of the same value.

So new housing on large suburban lots has been and continues to be a good deal economically for the buyers for all the reasons listed above. Probably the most important is not only do the U.S. Treasury and the State of Minnesota pay a good share of the new-housing cost to the purchaser, but newer housing on the edge usually appreciates faster than older housing closer in, as subsidies are capitalized.

Bottom line: The tax expendituresthat enhance the buying power of middle- and upper-middle class housing consumers vastly exceed subsidies to low-income individuals and households that come in the form of housing vouchers and Low-Income Housing Tax Credits.

(23) What are the local private organizations that promote and/or create varying housing options?

A:

- Organizations representing for-profit actors (e.g., BATC-Housing First Minnesota)

- Organizations representing nonprofit actors (e.g., Catholic Charities; Presbyterian Homes; Greater Minnesota Housing Fund; Minnesota Housing Partnership; Housing Justice Center; Common Bond Communities and others)

(24) What are the main institutional frameworks within which the housing process operates in the metro area and in Greater Minnesota?

A:

- The federal Internal Revenue Code (which changed most recently for tax year 2018 and subsequent years).

- State of Minnesota tax law influencing what kinds of housing will be allowed inside cities and what will be discouraged.

- Federal Housing Administration mortgage-loan insurance program.

- Mortgage-loan underwriting and the secondary mortgage market.

- State and local building codes, housing codes, zoning codes, development regulations (e.g., minimum lot sizes for houses), and specific development impact fees (such as the Metro Council's Sewer Access (SAC) Charges.

![]()

Make a tax-deductible gift to the Civic Caucus.

The Civic Caucus distributes its regular reports without charge. We require no dues or membership fees. We operate solely on your voluntary, tax-deductible gifts.

To make an online gift, go to www.givemn.org , a secure site maintained by several Minnesota foundations. Follow instructions to fill in your gift amount and credit card information. You may also give by check. Please make your check payable to "Civic Caucus" and send your contribution to Civic Caucus, 2104 Girard Ave. S., Minneapolis, MN 55405-2546.

Thank you for your support!