Iric Nathanson

Past battles over Minneapolis Charter reform provide insights for today's efforts

An interview on Minneapolis City Charter reform

January 29, 2021

Local historian Iric Nathanson illustrates past battles in Minneapolis over City Charter Reform, notably the valiant efforts of Mayor Don Fraser in the 1980s. Nathanson and the Civic Caucus interview group discuss how Fraser accomplished some helpful Charter reforms and the insights to be gained from the past, as Charter reform efforts are once again underway in Minneapolis.

Notes of the Discussion

(Responses are edited.)

Background

00:00 - The Civic Caucus (Janis Clay)

00:30 - Introduction (Paul Ostrow)

Ostrow: We are glad to be joined by Iric Nathanson, whose distinguished career as a public servant included service on the congressional staff of former U.S. Congressman and Minneapolis Mayor Don Fraser. Nathanson has become one of the most, and possibly the most, renowned Minneapolis historians, and has written six books, including a recent excellent biography of Mayor Fraser. [A full biography of Nathanson is included at the end of these notes.]

03:15 - Opening Remarks (Iric Nathanson)

Nathanson: I believe the stories of our recent past, while many of us have still lived through that era, need to be preserved. I hesitate to call myself a historian, but rather say I'm someone who writes about history, primarily the intersection between journalism and our recent local history.

In 1900, Minneapolis and St. Paul each had a referendum on the ballot to adopt a home-rule charter, so they didn't have to approach the state Legislature to make changes to their government structure. St. Paul passed its referendum that year, but the Minneapolis measure went down to defeat after a huge battle.

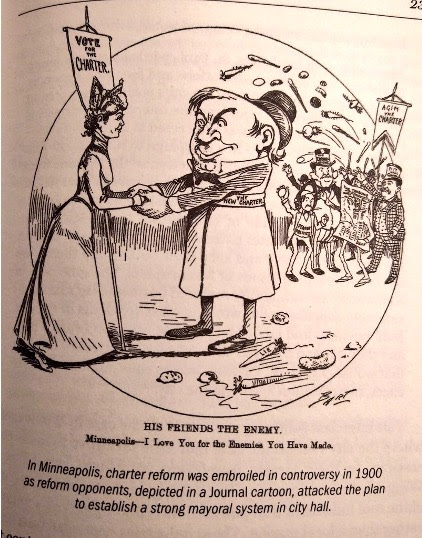

In Minneapolis , Charter reform was embroiled in controversy in 1900 as reform opponents, depicted in a Minneapolis Journal cartoon, attacked the plan to establish a strong mayoral system in city hall.

Charter opponents, primarily City Council members, are pictured throwing rotten fruit at the new Charter.

In St. Paul , civic unity prevailed as the city's various political forces, illustrated here in a Pioneer Press cartoon, worked together to approve a new Charter in 1900.

A Democrat, a Republican and an independent voter are depicted pushing a Charter steamroller down the road together.

Historian Mary Wingerd observed a difference between Minneapolis and St. Paul in this era in terms of political cohesiveness , and the impact on their ability to pass a home-rule charter.

Capitalist milling titans' poor treatment of their employees led to labor and political strife in Minneapolis. This created great difficulty in establishing a home-rule charter. In St. Paul, upon realizing their employees were also their main customers, the brewery business owners were encouraged to treat their employees better. Labor, management, religious leaders and business owners banded together to pass the home-rule charter in St. Paul.

Minneapolis tried and failed to pass a home-rule charter five times during the first two decades of the 20th century. (LIMS Minneapolis City Charter History) In 1920,the existing crazy-quilt, weak-mayor system was codified into a charter, which the voters finally approved.

The 1920 charter survived mostly unchanged in Minneapolis, with some reform efforts during the tenures of Mayor Hubert Humphrey (1945-1948) and Mayor Art Naftalin (1961-1969). There was little success at reforming this crazy-quilt system until the tenure of Mayor Don Fraser (1980-1993).

Fraser's swoop into city government set the stage for his conflict with the City Council, since they viewed him as an outsider from Washington. In 1978, Representative Don Fraser gave up his seat in the U.S. House to run for U.S. Senate, narrowly losing the Minnesota DFL primary. He then ran successfully for mayor of Minneapolis at the last minute, taking office in 1980.

The Executive Committee wasadded to the Minneapolis Charter by referendum in 1984 and was intended as a consultative body that would chart policy, review appointments, and come to consensus collegially. After great disputes between Fraser and City Council President Alice Rainville, this was devised as an informal power-sharing arrangement. Fraser got frustrated, since he was frequently outvoted on the Executive Committee, which consisted of the mayor, the City Council president, and three additional Council members.

In 1987, Fraser proposed a Charter amendment to make the mayor the presiding officer of the City Council. The Minneapolis Charter Commission refused to approve Fraser's proposed Charter amendment, resisting the strong-mayor push in line with the City Council. Fraser petitioned on the street for signatures to get his referendum on the ballot. The Charter Commission and City Council didn't like this, so they altered the wording and position of the referendum on the ballot. The proposal went down to defeat from the voters but came close to passage.

An avid machine tinkerer, Fraser took his interest in physical machines to the realm of government institutions. After being involved in Congressional and structural reform within the Democratic Party in Washington D.C., Fraser brought this interest to Minneapolis city government.

In 1988, as part of his last reelection campaign, Fraser created a nuanced Charter proposal that would allow the mayor to propose city department head appointments, with approval from the Executive Committee. But the Executive Committee couldn't submit a new name themselves. If they rejected the mayor's appointment, they would have to wait for the mayor to propose a new name.

This proposal was unpopular with the Charter Commission and the City Council, so Fraser again petitioned successfully to get this on the ballot. After clashing again with the City Council over ballot wording, Fraser did finally get this Charter referendum passed by the voters in 1988.

Discussion

20:0 8 - How did Fraser get his Charter reform efforts passed? (Pat Davies)

Nathanson: This issue was part of his mayoral campaign. He came up with a fund for advertising and used his bully pulpit to gain support for the reforms.

22:31 - In getting this reform passed, how did Fraser gain support among the city employees, who had been allied with the City Council in earlier elections? What was the role of the DFL party at this time on this issue? (Clarence Shallbetter)

Nathanson: I don't know whether the Minneapolis DFL at the time took a stance on this issue. Many City Council members came out against this at the time.

Lee Munnich: As a City Council member around this time, I became convinced that we needed a strong-mayor form of government. I broke with many of my City Council colleagues on this issue, who didn't want to give up their power.

25:48 - You wrote in your recent Star Tribune op-ed piece about St. Paul passing a strong-mayor form of government in 1970. How did they get this passed? (Lee Munnich)

Nathanson: By 1929, the labor/management unity that had passed St. Paul's Charter in 1900 had broken apart. There was a particularly violent streetcar workers' strike in 1917. I couldn't find much in the way of written records on the 1970 Charter change in St. Paul. They changed from a commission form of government with City Council members serving as department heads to a strong-mayor system. St. Paul seems more settled today on many dimensions than Minneapolis as a result of this change.

Minneapolis has a hybrid form of government with not quite a strong mayor, but moving in that direction. There is a lot of complexity and nuance to the Minneapolis structure that makes the process of governing difficult.

Lee Munnich: As I remember, the DFL was more focused on state and Congressional levels of government in 1970, and it wasn't very involved in this City Charter issue.

32:12 - Did we use to have a city manager in Minneapolis? (Pat Davies)

Nathanson: We have a City Coordinator, who is not a true city manager, since the Coordinator only oversees a narrow slice of city government. The Coordinator is just one of many department heads, one among equals.

Clarence Shallbetter: - The role of City Coordinator evolved to be a budget manager, which got a lot of clout.

Lee Munnich: There have been powerful City Coordinators, such as Tommy Thompson, but the City Council is still the City Coordinator's boss.

36:40 - Your biography of Don Fraser is a great resource. Can you elaborate on the battles during Fraser's time over how his proposed Charter changes would appear on the ballot? How might this take place in today's Charter-change efforts? (Janis Clay)

Nathanson: Fraser petitioned in 1989 to get his proposal on the ballot. He was ready to go to court to sue the City Council, because he felt the wording mischaracterized his proposal. They came to some kind of compromise after a big battle, but Fraser felt the council was trying to sabotage him with the wording.

40:41 - Were the relationships between the mayor and the police, and the City Council and the police, a source of tension or a reason for Fraser's interest in Charter change? (Paul Ostrow)

Nathanson: Police used to be more involved in city politics, and politicization of the Police Department was a concern for Fraser. Police officers used to dabble in city politics, the idea being if you campaigned for the person who became mayor, you might be rewarded with a promotion in the Police Department. Fraser wanted to take the police out of campaigning in this way.

44:19 - Was the mayor and/or the City Council involved significantly with the Minneapolis Police Federation in the development and approval of police contracts? (Clarence Shallbetter)

Nathanson: Police contracts did come before the Executive Committee, but I don't remember much public coverage of this issue. The policymakers of City Hall were compromised when it came to labor/management issues, because they needed the support of the unions for their own campaigns.

45:25 - Who represents the city in labor negotiations, and who has the authority to approve the Minneapolis police contracts? (T Williams)

Nathanson: I think the City Coordinator was the staff point person on the contracts. The Executive Committee would approve them and pass them onto the full City Council. What happened behind closed doors at the Executive Committee, we wouldn't know.

48:33 - Does the Board of Estimate and Taxation have any role in approving Minneapolis police contracts? (Lyndon Carlson)

Nathanson: I had never heard about their role in approving contracts. Minneapolis differs from St. Paul in that it has a Board of Estimate and Taxation. There was an effort to abolish it about 10 years ago which caused huge backlash, since this would have removed the Park Board's seat at the table in determining tax levies.

1:02:20 - How are the Minneapolis police contract provisions mirrored in state policy with respect to employee bargaining? Did the Police Federation get included in the arbitration method of negotiations as a result of its own advocacy? (Clarence Shallbetter)

Nathanson: Progressive DFLers can't appear to be anti-union. We shouldn't really call the Police Federation a union, because it's not part of the labor movement in the same way that service workers' unions are. These are complicated issues and politics is floating above all of this.

Lyndon Carlson: If you put PELRA [the Public Employment Labor Relations Act, the statute governing public sector collective bargaining in Minnesota] on the table for any discussion, you'll get strong pushback from labor unions.

Clarence Shallbetter: The question remains, how are you going to get any decisions by the chief enforced when it comes to the behavior of officers in the system?

Lee Munnich: Minneapolis used to have a residency requirement for police, and they got rid of this because there was a concentration of officers in particular city wards that had too much influence over contracts. It's interesting that now we see a different concern over police residency, since so many live outside the city.

1:11:46 - Part of the problem is that labor negotiations can be exempt from the Open Meeting Law and are done behind closed doors. (Comment from Paul Ostrow via Janis Clay)

1:12:44 - What makes labor negotiations exempt from the Open Meeting Law? (Helen Baer)

T Williams: Labor negotiations became an exception because labor wanted it this way, and they had the political power to make it happen. I think there are some good reasons for having the exception.

Lyndon Carlson: When PELRA was passed, both management and labor were concerned about negotiating in the fishbowl, and the difficulty of coming to an agreement if they were publicly making concessions. That resulted in their exemption from the Open Meeting Law. There was a change to this in the last legislative session, as to how public the hearings for employee discipline problems should be.

1:14:51 - Is it accurate to say in Minneapolis, there is nothing that mandates an elected body to hold closed-door discussions of labor negotiations, but rather this is a choice they can make permissively, based on judgment that the public interest is being served? (Paul Ostrow)

Paul Ostrow: It makes sense that disciplinary procedures are private, and these should be. However, I would argue in this case, having these closed-door negotiations is a crutch used by elected officials. I believe it would be in the public interest at this point to hold Police Federation negotiations open to the public.

1:16:21 - As a newspaper publisher in Greater Minnesota, I reported on three different school districts. They told me when their contract negotiation meetings would be, but they'd try to do things like holding the meetings at 6 a.m., hoping I wouldn't show up. But I came. (Comment from Dana Schroeder)

Biography

Iric Nathanson is a well-known local historian. He is the author of more than 30 articles and six books on Minnesota history. His 2010 book, Minneapolis in the Twentieth Century: the Growth of an American City, was a finalist for a Minnesota Book Award. Nathanson's articles have appeared in Minnesota History, Hennepin History, and the StarTribune. He also writes a history feature for the on-line daily MinnPost. His most recent book is a biography of Don Fraser, titled Minnesota's Quiet Crusader.

Nathanson was a public servant for a number of years. He served on the staff of former Congressman Don Fraser from 1967 to 1978. He then served in the Department of Housing and Urban Development in Washington, D.C. Following this, Nathanson was a staff member and leader of the Minneapolis Community Development Agency (MCDA) from 1983 to 2003.

Present for Zoom interview

Tom Abeles, John Adams, Helen Baer, Lyndon Carlson, Janis Clay (chair), Pat Davies, Paul Gilje, Lee Munnich, Iric Nathanson, Paul Ostrow, Dana Schroeder (associate director), Clarence Shallbetter, T Williams.